Donald Trump in 1997. Ron Galella / Getty Images Donald Trump in 1997. Ron Galella / Getty Images WEEK 8: Understanding others | WEEK 9: When you're passionate... | WEEK 10: The little things count Have you ever met a journalist that isn't passionate? Let's face it. Doing this job isn't going to make you rich. It isn't going to make you a better partner or spouse -- as a matter of fact, it will likely, at some point, take a toll on your personal relationships. You're going to miss friends' weddings because of the gig. Did I mention you aren't likely to get rich? So, why do we pour ourselves into this profession? Because we typically have a passion. Whether the passion is for social justice, politics, sports, racial equality or Beyonce, journalists are a passionate bunch. Last week, I wrote that journalists can't be objective, but best be fair and thorough. So, what happens when you have to be fair and thorough on something of which you are either passionately for, or passionately against? The answer is easier than you think. The answer is, YOU DO YOUR JOB. Let's say you are a Red Sox fan. How do you write a profile about Yankees shortstop Derek Jeter? You can't get rid of your fandom, nor do you need to do so. However, you must be able to look at Jeter's career - his fantastic statistics, his wins, the way he stayed out of trouble and seemed to be a solid teammate - and write a thorough piece. What if you are a Yankees fan writing the piece? You don't get to gush. You point out those statistics. You write about his positives, but you also address criticism - that maybe the team gave him too much toward the end of the career, that maybe he was closed off. As a student covering your school's team (even in the Frozen Four), a member of a Greek organization involved in the coverage of fraternity malfeasance, a Democrat at the GOP national convention... if you can't do it fairly, thoroughly and well balanced, be transparent -- tell your editors/producers, colleagues and your audience where you stand, if it is important, and/or recuse yourself. Why? Because we know you are passionate. Let's take a look at three great - and diverse! - stories on this fall's presidential election. This is a 1994 profile on Hillary Clinton published in The New Yorker. It is largely considered to the most thorough article written about her. Connie Bruck penned the piece and it was published while Clinton was First Lady. I could not find anything on how Bruck felt, but - regardless of her political leanings or feelings toward Clinton - Bruck was fair and thorough. This is what someone quoted in the article noticed: "Bruck got members of Congress, the White House staff, news people back in Little Rock, old classmates and seemingly every friend Hillary ever had to talk about her — gushing usually but sometimes too revealing." Bruck never got Clinton on record, but did get her husband - the president! - to talk for two hours. Here is one on Donald Trump from Playboy in 1997. Journalist Mark Bowen has described his time interviewing Trump as "long, awkward." He wasn't impressed with the real estate mogul, instead finding Trump to be "adolescent," "profane," "dishonest" and "unkind." Yet, would you ever have gathered that from the profile? No. Trump sounds like the over-the-top, boisterous personality he is. And, here is one (if you don't want to read either of those long reads) that PBS News Hour uses to describe a prevailing attitude in Rust Belt swing states. I particularly love the balance shown here, as well as the convergence of broadcasting and print journalism.

0 Comments

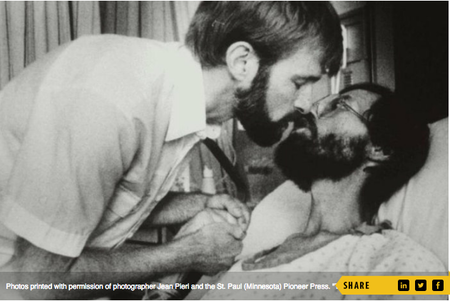

WEEK 7: What to leave in, what to leave out | WEEK 8: Understanding others | WEEK 9: When you're passionate... I do not believe that journalists can be objective. Despite being told that objectivity is a requirement for the job, I think it's impossible. No matter whom I interview, no matter what story I write, I can't not be a middle-aged white woman from the Midwest. It's impossible for me to shed my whiteness, my femaleness, my liberalness, my life experiences, my gayness, my privilege. Now, that doesn't mean I don't have to be fair. It doesn't mean I can't incorporate multiple opinions, angles and perspectives. As a matter of fact, knowing I can't not be myself, I best strive for fairness, completeness and diversity of opinions, angles and perspectives. So, how does one do this? How does a young, white, upper-middle class person fresh out of college cover the racial tensions plaguing our nation? How does a devout christian cover religious extremism? How does a Red Sox fan cover the Yankees? Let me start by telling you that asking the question in the first place matters. Multicultural flexibility and diverse sensibilities are necessary tools in your journalism toolbox. In 2006, three scholars edited a book called "The Authentic Voice," a text dedicated to reporting on race and ethnicity. (You can visit the corresponding website here.) Former editor of The Mercury News, David Yarnold, wrote in the book's forward: "In the early nineties, a group of Latino leaders angrily denounced a series we ran on wannabe gangbangers. They complained we only saw their community when trouble was brewing. And you know what? They were right. We hadn't reported regularly on that community's deep religious faith, on its steamy cuisine, on its mostly rotten schools and its devoted teachers, on its issues with a white-dominated immigration bureaucracy, or on its role models, many of whom had overcome poverty and were now showing others the path to success. In other words, we hadn't developed a context for our criticism. Without it, we were presenting a skewed view of their world. Moreover, we were causing them pain and undermining our reputation. There's another reason for creating the biggest tent possible, so that everyone in our communities can fit inside. The Bill of Rights charges us with watching over the powerful on behalf of every day people. That mandate to pursue social justice applies to all, not some, of our community. We're here to serve--and see--broadly." You have a responsibility to pursue social justice on behalf of all. This is your job. This is hard to fathom given the current partisanship/fragmentation of the media. It seems we have a network for people who consider themselves conservative and another for liberals, a network for people of color, a publication for millennials. Yes, media are nuanced and a practitioner must identify and understand the audience. Still, great journalists don't tip their hand in their stories. Rather, they report and write so well the audience has no idea how the reporter feels. Jacqui Banaszynkski is a white, female reporter from Wisconsin. While with the St. Paul Pioneer-Press in the late 80s, she won a Pulitzer Prize for her feature on a gay couple afflicted with AIDS. She isn't a gay man, nor is she a farmer, but her piece "AIDS in the Heartland" is written with compassion while still paying attention to detail. She grasps the politicization of the disease, all while shining a light on the horrors the disease inflicts upon the body. STILL LOOKING FOR MORE? While great reporters are fair, thorough and culturally sensitive, the more diversity in the newsroom, the more experiences we can tap into because, like I said, we can't not be ourselves. Check out Mirta Ojito's 2000 New York Times piece called "Best Friends, Worlds Apart." Ojito did, in fact, emigrate from Cuba to Miami. Her understanding of the process was critical to revealing much of the emotion in this story.  WEEK 6: Make your words sing | WEEK 7: What to leave in, what to leave out | WEEK 8: Understanding others In 1992, before I graduated from high school and prior to the birth, even, of my current students, the University of Notre Dame suffered a tragedy. The bus carrying the women's swimming & diving team, traveling from Evanston, Illinois to South Bend, Indiana after a dual meet at Northwest, crashed. The accident, in freezing weather, killed two young women. My students into Boston sports know of Leigh Montville, now a Boston Globe columnist. In 1992, though, he was a senior writer for Sports Illustrated. And, he wrote a story in which the details I still remember to this day 24 years later. Montville weaved these simple, but memorable details into this sad story. Before the bus crashed, the movie Dying Young, which starred Julia Roberts, had played. They ate pizza. They were in a "whiteout" when the bus crashed. The weight of the bus literally knocked the wind out of the two young women who died, suffocating them. The team had a phrase for practice that the members used when dealing with the deaths of their friends: "Cancel the pain." Folks, those are things I remember from originally reading the article. Montville creates the scene and delivers the detail. Notice his cadence -- and how it changes. (SI.com's "The Vault" does a really poor job with layout -- the paragraphs are all clumped together, but you can still see - and hear - the sentences.) Notice how he uses short, quick sentences. Then, uses longer, more descriptive sentences. Both, however, take you there whether Montville is describing injuries, or the Notre Dame community. He is somber in detailing a frantic emergency room scene, but follows it immediately up with a powerful, but almost humorous quotation. But, there is also something completely unique about this article. Montville inserts himself into the article. Granted, this is something I would probably put you on blast for if you did it for one of my assignments, but it turns out, one of the surviving swimmers was Montville's goddaughter. What do you think? Does it work in this article? I think it adds critical detail to the story, as well as a sentiment I might not otherwise grasp with such completeness. Montville even probes the ethical dilemma in the same article. Now, why do you think this works as I've described it here, but I would still not want it from my novice students? Because my students don't have the experience, yet, to understand what needs to be left in and what needs to be left out of a story. (The headline, here, I lifted from Kevin Van Valkenburg's syllabus.) Despite bringing himself into the story, Montville doesn't get preachy. Instead, he describes his feelings wondering if Kristin Heath was going to be OK, his awkwardness the first time he saw her after the accident. And, he asks the reader if he should even be mentioning this. But, these are the emotions of tragedy -- fear, longing, worry, anticipation, not knowing what to say. He delivers it masterfully and he does so because he knows exactly what he is doing, because he is a master of this craft. Give it a read. What do you think? And, how about that ending? That was something else that stuck with me. I can just see a guy shaking his head with a big smile and truly, really feeling such admiration and joy for a young woman who had gone through so much and come out on the other side. STILL LOOKING FOR MORE? Van Valkenburg posted this story from Kurt Streeter, "A Team Playing From the Rough," in the Baltimore Sun. This story cuts through race, privilege, class and tells us a story that invokes all of those things manifested in an unlikely high school golf team in East Baltimore. What is #QUreads? Each Monday, I will tweet a link to a blog post that will include a selected reading and an explanation of why you should read and study it. You can find it using the hashtag any time. My prediction is that, if you read and study these stories, you will be a better writer by the end of the summer. Granted, if you practice in a journal, read consistently, take note of style and think about what might the writer's decision-making process be, you will improve greatly. I'm just here to help the process along for you. Feel free to use the Comments section here or on Twitter to discuss the articles and writing techniques, to ask questions, or offer links to other great stories. |

2019 FIFA Women's World Cup: Media, Fandom, and Soccer's Biggest Stage is available online and in hardback from Palgrave Macmillan.

Molly Yanity, Ph.D.

|